A conference at Cosmos analyzed the state of the art of platform work and the various ways collective actions are trying to reclame the platforms and worker’s rights

Lucia Amorosi, Iraklis Dimitriadis, Sarrah Kassem, Vincenzo Maccarrone, Nicola Quondamatteo, Stefano Tortorici

It has been more than ten years since the platform economy began to take hold around the world. According to the estimates of the European Commission, nearly 28 million people in the EU worked for one or more digital platforms in 2021. By 2025, that number could reach 43 million.

Despite this exponential growth, most of the problems related to the platform economy remain unresolved. The majority of platform workers are employed through forms of (semi) self-employment, thus remaining excluded from the protections of employees. Pay is usually by piece, creating incentive systems that put workers’ health at risk. One example is the bonus on completed orders that Glovo offered this summer to its riders who chose to work in extreme heat, which was almost immediately withdrawn following the controversy it raised. But even initiatives aimed at protecting workers’ health, such as Apulia prohibiting delivery drivers from delivering orders during the hottest hours of the day, end up having a negative impact on workers who are paid on a piecework basis and therefore do not receive a salary.

The regulatory vacuum surrounding platform work continues to fuel informality and precariousness. The misclassification of the employment status and the replacement of employment contracts with unilateral terms of use have significantly undermined workers’ rights. It is not surprising that platform companies are actively lobbying to maintain these conditions, further strengthening their power and limiting that of workers.

Alongside the return of nineteenth-century practices of exploitation and the invention of ever-new ways to extract surplus value, digital platforms are producing an unprecedented accumulation of capital and control over our activities. An article by Kai-Hsin Hung in 2025 calculated the total value of platforms’ market capitalization as $31 trillion in December 2024, counting only the top 300 publicly traded technology companies. Eighty percent of this was invested in US companies, more than half of which, was invested in the Big Five in July 2025: Alphabet, Apple, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft. These platforms have enormous infrastructural power stemming from their ownership of software and cloud services, the material assets such as data centers and submarine cables, enormous environmental and energy resources that allow them to function, and hardware production that supports data extraction and processing.

Recent developments have demonstrated the enormous political weight that Big Tech companies exert on the US regime, from the obvious presence of their CEOs lined up behind Trump’s inauguration to the more subtle and aggressive techno-fascism of Musk and Thiel. Further studies have demonstrated the renewed convergence between military and digital trajectories, not least of which is the powerful role played by Big Tech in the Palestinian genocide economy, as highlighted in the Special Rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories Francesca Albanese’s report. These are actively involved in experimenting with targeting and policing programs on the Palestinian people, their direct annihilation through AI programs, and profiting from the “reconstruction” economy.

Over the last decades, there has been however an attempt to highlight the positive effects of digital platforms along the lines of two main narratives. The first argues that these tools offer workers greater flexibility and autonomy, allowing them to decide when and how much to work. The second attributes to platforms a role in formalizing activities that have historically been relegated to informality: from delivery work to domestic and care work, from taxi drivers to tasks including repairs and furniture assembly.

In the first case, the often highlighted autonomy clashes with increasingly pervasive forms of control, conveyed by digital technologies such as performance metrics and opaque algorithms. The apparent freedom to choose working hours translates, in fact, into total uncertainty regarding daily pay. A case in point is that of Uber drivers or riders, who receive opaque information on the calculation of compensation for each ride. The logic by which this is determined by an algorithm remains deliberately obscure and inaccessible.

In the second case, the promise of greater protection—similar to that enjoyed by regular employees—clashes with a very different reality. Although some aspects of work processes have been partially formalized (such as the traceability of electronic payments instead of cash, or the matching of supply and demand through a platform rather than word of mouth), a growing number of critical studies highlight how platforms actually contribute to a new wave of job insecurity and informalization. This often takes on additional forms for racialized and gendered work as in the case of domestic work.

Similar to the larger informal economy, gig economy workers are often forced to take care of their own health insurance, do not enjoy paid vacation or sick days, do not receive pension contributions, and are not compensated for downtime: the time between one ride and another for a rider or taxi driver, the time spent building a visible profile on the platform, or travel between homes for those who perform domestic work. The result is an increasingly widespread phenomenon: a worker who is apparently “free” but in reality subject to widespread control, deprived of essential rights and protections.

These issues become even more serious when the job insecurity that often characterizes platform work is combined, as is very often the case, with the broader insecurity of life that affects people who are marginalized for various reasons. Migrants, in particular, are the ones who most easily find employment through platforms: think of migrant delivery drivers or domestic workers, who find work through these tools.

In the constant pursuit of profit, the social marginalization of people—based on specific gender relations, race, migrant backgrounds, and age—represents a gold mine to the platform economy. While it is no longer entirely true that only migrants perform certain types of work, what remains indisputable is that specific social relations underpin hierarchical stratifications in which every difference justifies particularly degrading working conditions. This makes attempts at recomposition and collective action inside and outside trade unions particularly difficult. This is even more significant in contexts where the informal economy plays a predominant role—such as in countries in the Global South, where a growing number of workers take on the micro-tasks that keep search engines, social media, and artificial intelligence running.

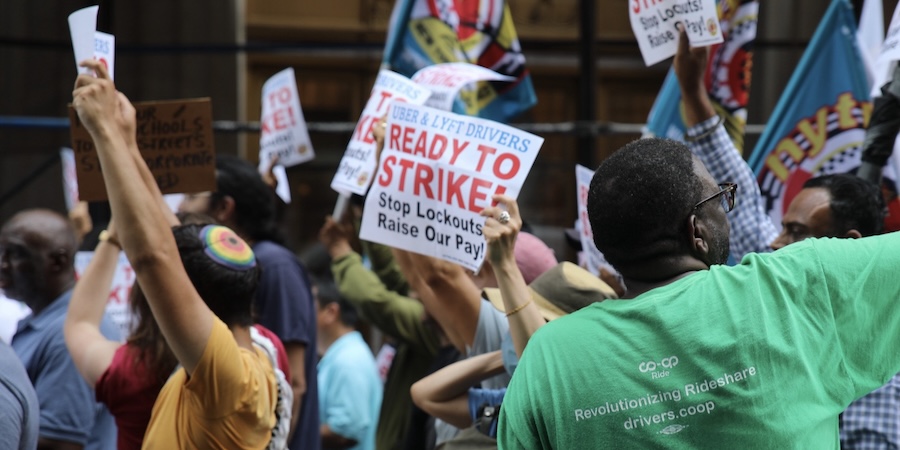

However, there is no shortage of forms of resistance and attempts to reclaim the platforms. A conference at the Scuola Normale Superiore on June 26 and 27 explored new aspects of this power by looking at the struggles against it, but focused mainly on the various actors involved in countering this power: social movements, trade unions, benchmarking projects, consumer and business associations, legislative attempts, and solidarity-based digital economies (digital commons, artificial intelligence and platform cooperatives, DAOs, AI for the people). The challenge, which is still very much open, is to understand what can be done, who the actors are and what attempts are effectively countering the power of platforms, and where fruitful convergences can be built.

28/10/2025

Journal Article - 2025

Journal Article - 2023

Journal Article - 2023

Journal Article - 2023

Journal Article - 2023

Monograph - 2023

Monograph - 2022

Monograph - 2022

Journal Article - 2021

Journal Article - 2021