An exhibition and a public meeting: the housing struggles of the 1970s and the occupation of Palazzo Vegni, the situation of the Florentine housing movements today

The new Florentine headquarters of the Scuola Normale has an ancient history and a contemporary one that is worth remembering because it is intertwined with the events that have been affecting historic central areas of Italian and European cities for some years now. In the mid-1970s, the medieval Palazzo Vegni was in fact occupied by the housing movements. To recall that event and reflect on the present, an exhibition and open meeting was organized last March 18th. The SNS’s Cosmos Lab, researching and studying social mobilizations for some months has also been housed in this important place for the history of the social movements in Florence, and it was worth pointing out this convergence.

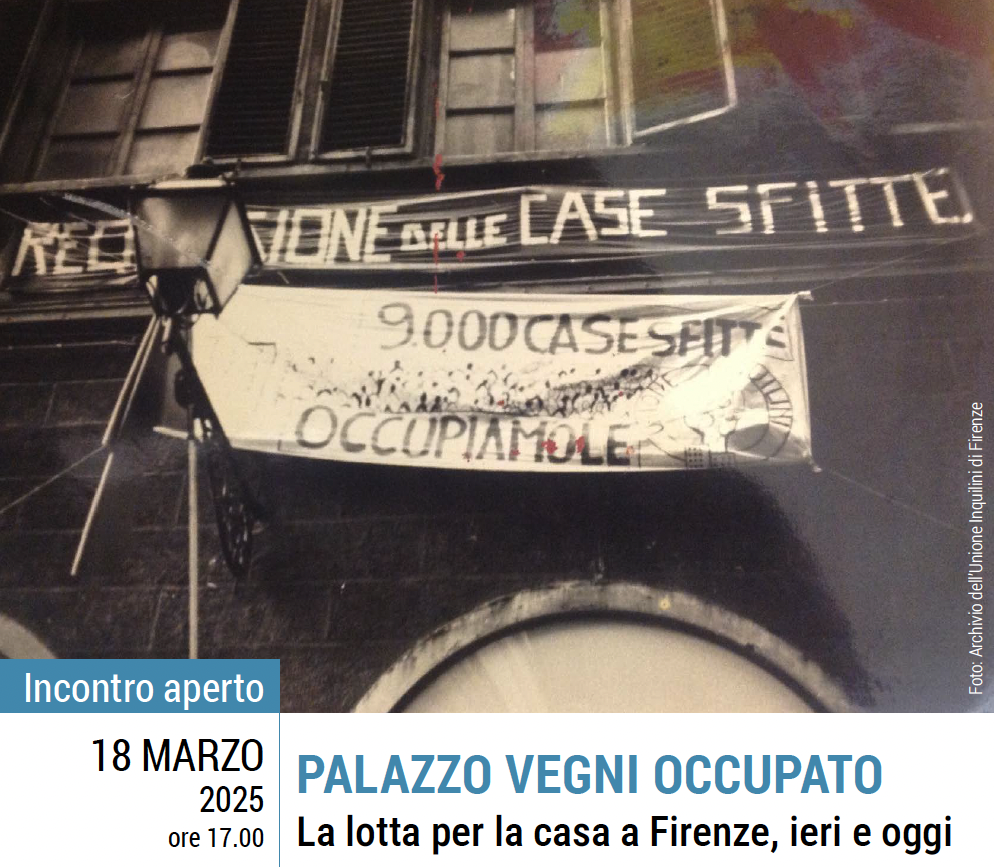

The exhibition curated by Herbert Reiter (SNS) is a brief journey through the history of that occupation, photos and outward communication materials that point out how in the years following the economic boom and internal migrations to urban centers, several cities found themselves with more citizens than roofs – and as recalled during the meeting, the problem was so great that in 1969 the Unions called a general strike to fight for the right to decent housing. The photos in the exhibition communicate the desire to create shared spaces that were not just homes, but envisaged common areas and services. In 1975 the idea was as well the need to stop what was the process of gentrification of historic city centers – now replaced by their transformation into touristic theme parks. The old posters also show the desire to communicate with the neighborhood what was being done, seeking its solidarity and pointing out that it was not a foreign body settling in a space but a piece of society that aimed at creating a public space for the neighborhood as well.

During the discussion, Donatella Della Porta, the Cosmos Lab’s director, pointed out how the housing movements today are very different from the past because their sole issue is not just the right to have a roof over one’s head, but to curb the renting out not only of houses for short rentals, but of everything around it: tourists are proposed what is called “the urban experience”, not just accommodation for the night. The transformation of Florence into a tourist destination is more impactful and rapid than gentrification and deforms the fabric of the territory as a whole. This also changes the way social movements protest and organize. There is a difference between historical housing movements, which still defend and deal with economic and social marginality, and those who protest or investigate the issue of tourisfication, which have demands that are in some respects broader.

Among the things that have changed is also the ability of institutions to listen and respond: while the occupation season of the 1970s generated a law on the possibility of requisitioning empty spaces by municipalities, and local institutions did connect with occupations as these signaled a real issue, nowadays the so called 2014 Lupi law prohibits supplying occupied spaces.

Among those who spoke was Pietro Pierri, from the Union of Tenants, who remembers that season for having lived through it as a child and recalled how a law for the possibility of requisitioning by municipalities and new investments in social housing was also born from it. “There was also the emblematic value of re-appropriation of public space and marking the desire of the less well-off classes to remain in the historic center, and those were years of possible interlocution with municipal administrations: occupations were tolerated as forms of political participation and social claim”. Another change lies in the social structure: back then families had not accumulated resources and home ownership was much less widespread, there were no economic parachutes (an observation that perhaps explains why so many migrants participate in contemporary occupations).

Valentina Ferrucci (president of the Casa del Popolo di San Niccolò) explained how hers is also an experience that gathers the inheritance of the 1970s season and that today she sees herself having to work to stem the transformation due to touristicisation: ‘What was once a neighbourhood of council houses has been transformed (…) The spread of the value of rent even in small and middle-class areas makes it difficult for those who work or come to work in the city to afford rent (e.g. bus drivers, nurses). And then there is the phenomenon of short rentals which disrupts relations in the neighbourhood. The Committee, on the other hand, tries to maintain some spaces (public gardens, clinics) to prevent people from leaving, because even those who can afford to stay risk choosing abandonment not for economic reasons but for lack of social fabric.

There remains the knot of institutions, which deal with certain issues in an episodic manner and without having an idea of how to deal with it at the root.

Massimo Torelli, of the Comitato Salviamo Firenze X Viverci, instead, explained the work of a group that works to report, raise awareness and protest against the touristy situation, recounting a public initiative in front of the Ex Caserma Ferrucci where the Committee could not even find a resident to display a banner in the window because there are no more residents. All the participants told of a certain impermeability of the institutions that seem to lack an idea of the city.

Journal Article - 2025

Journal Article - 2023

Journal Article - 2023

Journal Article - 2023

Journal Article - 2023

Monograph - 2023

Monograph - 2022

Monograph - 2022

Journal Article - 2021

Journal Article - 2021